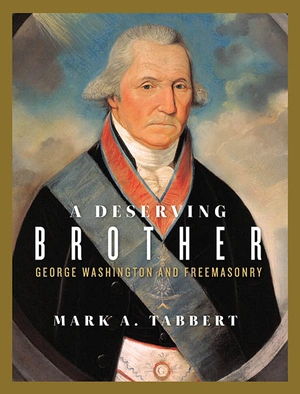

Beta Chi Alumnus Authors Book on Washington and Freemasonry

Recently in the spotlight at the University of Virginia for his newest work, Director of Archives and Exhibits at the George Washington National Masonic Memorial Mark A. Tabbert (Beta Chi/Allegheny 1986) sat down to discuss A Deserving Brother: George Washington and Freemasonry. Brother Tabbert also authored American Freemasons: Three Centuries of Building Communities.

The following interview appeared in the UVA Press Author’s Corner which can be found here, reprinted courtesy of University of Virginia Press.

What inspired you to write this book?

When I was hired by the George Washington Masonic National Memorial Association in 2005, I assumed the nearly century-old institution had somewhere along the way collected all there was to know about George Washington the Freemason. After all, the 1752 meeting minute book of the Lodge at Fredericksburg that recorded Washington’s initiation still existed. Most of his correspondence with Freemasons is published, and many artifacts, such as his Masonic apron, are publicly displayed. I was even told by a colleague there was no more evidence to be found.

But soon after starting work at the Memorial I realized my assumptions were wrong. Although most of the evidence of Washington’s Masonic membership was documented, there was no comprehensive analysis of it. I could find no academic paper or publication on the subject on any level. A professor told me the standard work was John J. Lanier’s Washington: The Great American Mason (1922)—a book even I knew was unreliable.

The Memorial Association’s library holdings were even more disappointing. Most of the standard Masonic publications are re-works of Sydney Hayden’s Washington and his Masonic Compeers (1866). Only Julius F. Sachse’s Washington’s Masonic Correspondence (1915) attempted a systematic presentation. Of the scores of secondary articles available, 90 percent were cribbed from these standard works or were outright fiction. The best chronology of Washington’s Masonic activities and correspondence was found on a Masonic research website.

It was not until the Memorial Association’s 2014 Washington’s Birthday Symposium that my disappointments were challenged. One of that year’s speakers, Professor Scott Casper, innocently asked me what book he should read on Washington’s Masonic membership. After patiently listening to my long-winded rant, he responded that I was the obvious solution to my own problem. Stunned by such a charge, it took me a few months before I accepted this fact and set to work.

What did you learn and what are you hoping readers will learn from your book?

The book’s purpose is to gather all known evidence of George Washington’s membership in, and interaction with Freemasonry. By presenting all available evidence, it affirms his life-long membership in, and support of Freemasonry, while hopefully dispelling numerous misconceptions, tall-tales, and falsehoods. By contextualizing George Washington’s Masonic membership and, after 1778, his patronage of American Freemasonry, this book reveals how both Washington and Freemasonry grew and matured between 1752 and 1799. The book may be seen as a case study that supports both Gordon Wood’s The Radicalism of the American Revolution (1993) and Stephen Bullock’s Revolutionary Brotherhood: Freemasonry and the Transformation of the American Social Order, 1730-1840 (1996).

What surprised you the most in the process of writing your book?

That no scholar had ever done such research on George Washington. Nearly everything within the book had been identified over the last 150 years and yet no serious book on the subject had been written in nearly 70 years and the last major academic book on Washington and early American Freemasonry was Bullock’s “Revolutionary Brotherhood” over 25 years ago.

What’s your favorite anecdote from your book?

In late January 1800, Tobias Lear, the Washingtons’ private secretary, opened a letter from the Freemasons of Massachusetts addressed to the widow Martha Washington. In it, John Warren, Paul Revere, and Josiah Bartlett informed her of their resolve to commission a gold urn that would hold a lock of General Washington’s hair. They hoped that Mrs. Washington would grant their request “that it be preserved with the jewels of the society.” Responding for the widow, Tobias Lear did indeed enclose a lock of Washington’s hair and wrote, “Mrs. Washington begs me to assure you that she views with gratitude the tribute of respect and affection paid to the memory of her dear deceased husband.”

The lock of hair arrived in Massachusetts before February 11, 1800; on that date it was then carried within a large marble urn in solemn procession through the streets of Boston. Like Freemasons throughout the nation, the Massachusetts brethren held a special meeting to render “funeral honors” for their departed brother. Within the next two years Paul Revere cast a solid gold urn for the hair. As promised, it remains “with the jewels of the society” to this day.

What’s next?

Next month, I am publishing the Almanac of American Freemasonry, 2 volumes: 1730-1774, 1775-1799. These two books provide a detailed account of every known Masonic activity, lodge, and publication in North America. I am also working on a short history of the George Washington Masonic National Memorial Association which was founded in 1910 and built the George Washington Masonic National Memorial between 1922 and 1932.

© University of Virginia Press